- Home

- Kaela Rivera

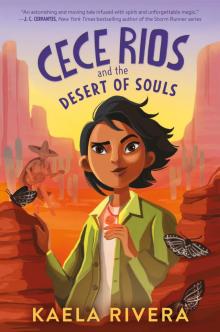

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls Read online

Dedication

In honor of my abuelo, who shared with me

his precious memories and stories.

In defense of my mother, who has always had

a soul as strong as water.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1. The Criatura of Progeny and Stars

2. Noche de Muerte

3. El Sombrerón

4. The Burning Familia

5. The Limpia

6. The Path of Brujas

7. The Makings of a Bruja

8. The Soul Debt

9. The First Fire

10. The Moth and the Coyote

11. The Bruja Fights

12. The Fighting Ring

13. The Life Favor

14. The Lion

15. The Lion Tamer

16. The Reluctant Allies

17. The Cerros of the Past

18. The Sun Sanctuary

19. Hawk Hunting

20. Kit Fox

21. The Fox Test

22. The Tale of the Great Namer

23. The Bonds of Criaturas

24. The Will of Cecelia Rios

25. The Sign of the Binding

26. A Soul Like Water

27. Brujo Rodrigo the Soul Stealer

28. The Braided Sister

29. La Casa de Familia

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

The Criatura of Progeny and Stars

I was seven years old when I met my first criatura.

I was wandering through the cerros—the hills of the desert beyond town—at night, barely avoiding low heads of cactus. In the dark, their spines looked more menacing than they did under the sun. But then, I was a child. Everything looked menacing in the dark.

I was lost. No matter where I turned, I couldn’t see the light of town. The other children had left me hours ago. I should have gone home with them, but I’d wanted to watch the sunset by myself.

I should have known better. It was winter, and with winter came danger.

Not because of the cold. But because it was los meses de la criatura—the criatura months.

Since before I could remember, Mamá had taught me the legends of the criaturas. They were creatures unlike humans, children of the Desert goddess, who the Great Namer created from dust and words. Mama taught me the difference between animal criaturas, who were made to fill the desert, and dark criaturas, who were made to attack the descendants of the Sun god—us. But her advice for dealing with both types was the same.

“You must steal their souls and command them to leave you,” she’d always said. “For you cannot outrun a criatura once it sets its sights on you.”

Her words seemed to wrap around my throat as I turned in the darkness, trying to find the distant outline of my town.

“Are you lost, human child?”

I gasped and whirled around, clutching my shirt. Out of the shadow cast by the hill, a creature slipped into view.

She walked forward on legs of flesh, just as smooth and brown as anyone’s in town. Her skirt was bright with reds and greens and blues. Her headdress shimmered with sleek owl and quetzal feathers to match, and its ornate moonstone beads swayed from side to side. But from the waist up, she was bones.

My voice froze in my throat. Her face was a skull, her jaw hanging just slightly open, as if ready to speak. Her eyes were empty black sockets, but I could feel them on me. I met their gaze, craning my head back in silent terror as she stopped in front of me.

It was Tzitzimitl. The Criatura of Stars and Devouring—a dark criatura.

Her lanky shadow fell over me in stripes, the gaps in her rib bones letting through beams of moonlight. Her jaw opened, and a voice came out of the motionless cavity: “You are far from where your people dwell in the once-great city of Tierra del Sol. Surely you are lost.”

My heart hammered so loudly I was sure Tzitzimitl would hear it and try to bite it out of my chest. I crossed my arms over myself and stumbled back a few steps.

“Don’t eat me!” I turned to run, but bony fingers wrapped around my shoulder before I got the chance.

Tzitzimitl’s strength was irresistible. “You do not want to wander through Mother Desert’s land alone, human child,” she said. “Here, criaturas roam freely for two more months. And La Llorona is loose in your world right now—she will drown you, or snake criaturas will eat you.”

I shook under her grasp. “P-please. I just want to go home.”

She cocked her skull, and her headdress shifted so its metallic stars clattered. “I will take you home.” She offered her bony hand. I stared at the fingers. “Don’t you know you can trust me, human child? I am Tzitzimitl. The Great Namer made me the protector of human children.”

Mamá had always said that criaturas would kill me. La Llorona would drown children in rivers, and Golden Eagle would snatch us away in his talons. El Sombrerón would steal daughters from their families, and the Gray Wolf would feast on the lost.

But . . . wouldn’t Tzitzimitl have hurt me by now if she were bad?

Slowly, I put my hand in hers. Her bones closed over my soft skin carefully, and she led me in a new direction.

“What is your name, human child?” she asked as we wandered between scrub and cacti.

I stared up at her. She wore a necklace that flashed in the moonlight. The simple stone on leather swung with every step we took. “Um . . . Cece. Cece Rios.”

“Another Rios,” she said. “I believe humans carry their names from one mother to another, correct? Your family has a history with criaturas, then. Do you know of Catrina Rios? In Devil’s Alley, they call her Catrina, Cager of Souls.”

Mamá had mentioned her once, but she hadn’t been very happy about it. “Is she my mom’s sister? My tía?”

“I do not know your mother.” She pulled me sideways before I could step on a sleeping snake. “But you share a last name, and you have her eyes. Perhaps she is your tía. Though I think you do not share the same heart.”

As we walked, my muscles slowly relaxed. Tzitzimitl didn’t do any of the things Mamá said criaturas did. She didn’t try to eat me. She didn’t try to drown me or lure me into a volcano. And after ten minutes, the town lights appeared in the distance—so I knew she was helping me after all.

I jumped up and down, pointing out the distant buildings. “That’s it! That’s Tierra del Sol!”

Tzitzimitl smiled down at me, her soul necklace swinging with my movement. At least, I thought she was trying to smile. It was hard to tell since she didn’t have lips.

“Tzitzimitl, can I ask you something?” I asked as we continued toward town.

“You may. Though I can’t promise I will answer.”

I pouted. “Mamá’s books said you were the Devourer. I don’t know exactly what that means, but it sounds bad. Why are you helping me?”

“Ah,” she said, and then didn’t speak for a long time.

After several unbearable moments, I shook her arm. “Well?” I asked.

The town lights grew brighter, each building like a lantern warming the edges of the desert. We crossed into the town’s shady, abandoned outskirts—the Ruins, Mamá called the area, left over from an ancient battle with criaturas. Large, empty husks of adobe buildings lined us left and right as we walked. But I kept my eyes on the lights. They were bright beneath the shadows of the cone-shaped oil wells lying far, far on the other side of town.

I’d never been out in that direction, but Papá said the oil fields l

ay all the way outside the Ruins that ringed my town, toward the east. And when he got a job there, he’d make enough money to build us a real house out of adobe.

Tzitzimitl’s fingers closed more tightly around mine. I looked up at her again.

“When the moon blacks out the sun, and Naked Man trembles in wonder at the heavens,” she said, using the name our legends used for humankind, “I am called to be the Devourer. It’s what I was named for. But I was also named the Protector of Progeny, the keeper of Naked Man’s children.”

I stared up at her as the worn, dirt road leading through the Ruins and into town appeared beneath our feet.

“I don’t get it,” I said. “How can you be both?”

“I wonder the same thing sometimes.” She sighed and patted my head with her other hand. “But it was the name given to me, so it is what I am. Only the Great Namer knows why.”

The Great Namer. I scrunched up my forehead as we reached the edge where the Ruins met my town. Warm yellow light fell over us as we crossed over. Mamá had definitely told me about the Great Namer before, hadn’t she?

“You mean Coyote!” I exclaimed when I remembered his other name.

Tzitzimitl flinched. “Shh, child!” I pulled my shoulders up to my ears. Her stance relaxed when she saw no one was around, and she nudged me to start walking again. I followed quietly.

“That is his name,” she said in a hushed tone.

“He’s my favorite,” I whispered. “Out of all the legends, I like Coyote’s the best.” Then I straightened up. “Oh, but yours is nice too, Tzitzimitl. Well, not nice exactly . . .”

I paused and looked up at her. The Devourer, leading me safely home? I squinted as I thought about it. She couldn’t be both. So she must be what I saw—the one who was nice enough to bring me home.

We entered the town square, and she glanced across the many avenues. “Where is your home, mija?” she asked.

I was about to point to the street when we heard a voice behind us.

“Miguel, she must be here somewhere. She knows better than to leave town—”

“Quiet. We will find her.”

The voices piled up into noise. I turned around, and Tzitzimitl let my hand slip out of hers.

From one of the streets behind us, Mamá and Papá appeared at the head of a great party of people. They held torches high, and the square was soon flooded with orange firelight. I shouted, “Mamá!”

Their heads swung toward us. Tzitzimitl took a step back.

“Mamá, Papá!” I called, throwing my arms up in the air. Their mouths dropped open as they spotted me. I ran forward, laughing. I’d missed my familia so much—

“A criatura!” Mamá screeched.

She and Papá dove past me toward Tzitzimitl. I flinched as they and the party of torchbearers flooded by. Without hesitation, they mobbed my friend, pulling her under their mass of strength.

At first, she fought back. She delivered powerful blows with her bony arms. She tossed some to the side. She even grabbed the man nearest her and opened her jaw wide. Someone screamed as her teeth aimed for the man’s shoulder. My stomach suddenly knotted up. She wasn’t going to devour him, was she? She was good. She wouldn’t.

Just before she bit down, her wide sockets stopped on me. I looked at her. And held my breath. And hoped.

Slowly, her bony fingers released the man. She stopped fighting. Immediately, the adults yanked her under a mass of torches and rope.

I dove into the crowd. “Don’t hurt her!” I filled my lungs to the brim and let out a scream: “Stop it!”

I found Papá and dug my fingers into his belt. He looked down at me, over his shoulder. His dark eyebrows crushed downward as he shoved me away from the fight. “Stay back, Cece!”

At the center of mayhem, Mamá reached down, gripped the necklace I’d noticed swinging from Tzitzimitl’s neck bone earlier, and yanked. The leather snapped. Tzitzimitl let out a painful-sounding gasp.

“Call the head of police!” Papá cried out as Mamá gave him the stone. “We will kill her tonight, before she can lure any more of our children away.”

“No!” I said, but the mob still dragged Tzitzimitl away.

Mamá crouched down beside me and turned my face to hers. “Cece, calm down, pepita. You’re safe now.”

I shook my head. “She’s not bad, Mamá. You—can’t—hurt her!”

Mamá’s hands froze on my face. “Mija,” she said, her voice like iron. “Criaturas are dangerous. If we do not destroy them when they come after us, they will overrun our people as they did in the days when the curanderas failed.” She gripped my face. “You must not cry! You must not be weak.” She gave my chest a hard pat. “You are a Rios, a descendant of the Sun god. You cannot let your tears make you more water than fire.”

I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew I didn’t like it. So I pulled away and ran.

The crowd had finished tying Tzitzimitl to the criminal’s post in the center of the town square, her wrist bones bound in a knotted wad of rope. Papá was speaking to the head of police, who was still in his pajamas. I ran up behind Papá and snatched Tzitzimitl’s soul stone and a knife from his back pocket. Fortunately, he didn’t notice.

I raced toward Tzitzimitl. Her chin lifted at my approach.

“Cece!” Mamá roared. “Cece, you stay away from that criatura!”

I skidded to a stop and cut her free.

Tzitzimitl stood on her muscular brown legs. The townspeople rounded on us.

“She let it free!” someone hollered.

Everyone surged forward. I offered her the soul stone. Where it rested in my palm, there was a tingly, warm sensation, the way I always felt when I looked up at the stars at night. Tzitzimitl took it from me in a clatter of stone and bone, already moving toward the outskirts of town.

But as she did, she looked at me.

“I am the Protector of Progeny, the Criatura of Stars and Devouring,” she said, her voice booming over the noise of the mob. It was so powerful, the townspeople fell silent, and they halted suddenly a couple of feet behind me. “I was named to see into the souls of children. And this day, I tell you, Cece Rios, that you have been blessed with a soul like water. None shall have power to burn you or make you ash.”

And then she fled.

Crisp, cool air settled on me after her words. My heart swelled. Then, as if breaking out of a trance, the crowd rushed past me after Tzitzimitl’s rapid escape. Angry yells replaced the cool, peaceful feeling in the air. Someone’s hand grabbed my face and shoved me into the ground.

In the dirt, I prayed to the Sun god that Tzitzimitl would not be taken. I prayed that Papá would not be angry. I prayed the townspeople would understand what I’d done.

The head of police marched over to Mamá, and the two screamed at each other. “I refuse to have another traitor like your sister in this town!” he spat. “You Rios women all end up the same. Go bury your daughter as a sacrifice to the Desert—”

Mamá straightened up furiously. “She will not be a bruja!”

“You heard the criatura’s curse! It is only a matter of time until your daughter’s weak heart betrays us.”

“She will not!” she said. “I will save my hija from this curse, or Ocean take me.”

The head of police went silent, stunned. No one in Tierra del Sol liked to speak of the Ocean goddess, with one exception—life-or-death oaths. In the face of that vow, the head of police had no choice but to believe Mamá and let me stay in town.

But no one would ever forgive me for the day I revealed myself to be the town’s weakest link—the day I had mercy on our ancient enemy.

2

Noche de Muerte

My sister and I ran toward the fiesta, our dresses trailing us like nervous flames.

“Juana, wait for me!” I called, panting. She had lifted her skirts so only the back swept the flat dirt road between our town’s adobe houses. “I still have to paint your threat marks! You can’t dance with

out them!”

Juana skated to a stop. “Just hand me the nocheztli, I’ll do it.”

I clutched the paint jar and slowed. “Mamá said she wanted me to practice painting you. I’m not going to mess it up, okay? Just trust me.”

Juana rolled her eyes and sighed. Ever since she’d turned fifteen and had finally become a woman, she’d been doing that a lot. I bit my lip to stop from saying anything. Tonight, her dream of being selected for the yearly Amenazante dance was finally coming true. She would be on full display as she defended our town from the dangers that would soon awaken in the desert. And I didn’t want to ruin her night with—well, with me being me.

Juana saw my face and stalked over. “Fine, fine. I just wish you would worry more about yourself.” She sighed as I dipped my fingers in the paint. “You didn’t even put fire opal in your hair to protect yourself, you were so busy with my skirts. Everyone’s going to think you’re a fool for being so unprepared.” Her mouth slanted sideways.

I flinched but tried to cover it up with a shrug. After all, the town already thought I was a fool.

I lifted my fingers to Juana’s face. I was nearly as tall as she was already, even though I was almost three years younger. Her eyes grew harder, sharper, as I framed them in the red blood of the prickly pear—nocheztli, the dancer’s war paint.

“Done?” she huffed.

I stepped back and smiled. Juana’s black hair crowned her head in a voluptuous bun, ringed with beads of bright fire opal, and a silk red rose I’d made perched on its top left. It matched the full skirt that swayed like flames around Juana’s ankles.

With nocheztli’s red streaks finally cutting across her face and bare shoulders, she was living fire. She needed to be for the dance she was about to do—the Amenazante dance, where the fiercest women in our town gathered to frighten away the criaturas that would soon plague the desert.

I squeezed the paint jar in my hands. “You look amazing.”

“Thanks.” She smiled and patted the top of my loose hair. “You did a pretty good job helping me out this year. But try to pay attention to yourself too, okay? In a couple years, you’ll be a woman, and if you impress the dancing committee enough, you could be invited to do the Amenazante dance too. Everyone would have to respect you then.”

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls