- Home

- Kaela Rivera

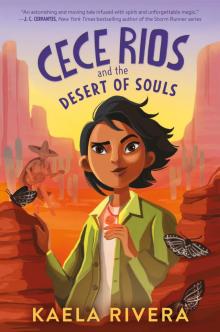

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls Page 4

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls Read online

Page 4

“Are we going through the back door again?” I asked quietly.

“Sí,” she whispered. “Now hush until we’re inside.”

I frowned to myself. I loved how peaceful it was inside the Sun Sanctuary, but because I was me, I’d only been allowed to come a handful of times, and never through the front door.

We took a last turn, and suddenly the Sun Sanctuary rose above us, its golden dome and white-painted brick clean and welcoming. It wasn’t a huge building—only about double the size of our small house—but it was taller than most with three floors of ascending stained glass windows. I tilted my head back to better take in the scenes they depicted. Some had people dancing under the Sun, others animals frolicking across the Desert, others showing people bowed under the Moon, and a chosen few depicted people swaying among Ocean’s waves. I stared at those windows the longest. That was something I never understood about the Sun Sanctuary—why all the gods, Desert goddess, Moon goddess, and even Ocean goddess, were included in the Sun god’s dedicated haven.

When I’d asked Mamá that before, she told me the Sun Sanctuary contained many mysteries. It was the oldest building in Tierra del Sol, nearly six hundred years old, and there were many ancient stories recorded in it that we didn’t remember or need anymore.

That didn’t sound right to me, but it was the only explanation I’d ever gotten.

“Come on, Cece, no daydreaming.” Mamá tapped my head. I looked away from the windows to find us at the back entrance. A red-painted wood door waited up a couple of concrete steps for us. I climbed them first and knocked gently.

The door opened to reveal Dominga del Sol.

The old woman looked a little tired, but she smiled at us both. “Axochitl and little Cecelia! My, I must have done something good for the Sun god to bless me with the two of you before he’s even risen this morning.”

Mamá didn’t look nearly as happy to see her. “Dominga del Sol, can we come in?”

Dominga del Sol stepped aside to let us in, and Mamá closed the door behind us.

“I’m sure you’ve heard what happened last night,” Mamá said. Her voice was low and curt.

Dominga del Sol rested a hand to her heart. “Yes. I’m sorry about Juana—”

“Cece was there when El Sombrerón took her,” Mamá said, and the sorrow rose in my chest like a geyser. “I need you to perform a limpia for her.”

I wasn’t sure whether it was the low light or the sternness in Mamá’s voice, but Dominga del Sol’s mouth hardened at the edges.

“I thought you didn’t believe in the power of the curanderas,” she said. “Isn’t that why you refused to bring your mamá to me when she was hurt?”

Mamá straightened up, eyes harder, face sharper, than Dominga del Sol’s could ever be. “I don’t believe in it,” she snapped.

“Then why are you here?”

I looked between the two women, a clash of firmness and fierceness.

“You know about Cece’s curse,” Mamá said softly. Somehow, the more quietly she spoke, the louder her voice felt. “Curandera magic failed our people. But my mamá believed in it.” She met Dominga del Sol’s unwavering gaze. “So, just in case, and for her sake, I’m asking you to try. It’s better than nothing.”

The beginning of morning slowly swept the nearest window with gray light. It caught in Mamá’s eyes and made them glow. Dominga del Sol’s mouth softened into sadness. But she nodded.

“All right,” she said. “Help me prepare the herbs. Did you bring the book?”

Mamá passed Dominga del Sol the book we’d found earlier and pulled out ingredients as Dominga del Sol named them. Then, they instructed me to undress. I peeled off my dress and waited in the chilly laundry room in my underclothes, listening to the hiss of steaming water as Dominga del Sol filled a pot from the tap. She hefted it onto the counter afterward, stirring in some cooler, fresh water, and outstretched her hand. Mamá poured the ingredients into her palm as she asked for them.

“Rosemary to clear the eyes,” Dominga del Sol whispered as she poured in the leaves. “Basil to protect the skin. Morning glories to bless the mind with truth—”

“And tobacco, to heal from the darkness,” I finished the chant.

I was surprised I still remembered the words from the last limpia she had given me. For some reason, they’d come so easily. Dominga del Sol looked down at me, and her sad face seemed to gain some life back.

“Very good, mija,” she said. “The curandera’s words feel natural to you, hm?”

Mamá scowled. “Don’t fill my hija’s head with nonsense, Dominga del Sol.”

“Sí, está bien. Here, mija. Come stand by the drain.” Dominga del Sol pulled the pot off of the counter.

I planted my feet over the drain in the stone floor. I couldn’t help feeling small and unwanted there, shivering in my underclothes, hidden away in the laundry room so that no one would know I was there.

“Axochitl, could you help me?” Dominga del Sol asked.

Mamá came and helped her heft the pot over my head. After the count of three, they tipped it over me.

Bright tingles of hot and cold rushed down my skin. The water rained down until all my worries, fears, and hurts were chased away. And then suddenly, it was done, and I was coughing and spluttering to get the residue out of my mouth.

Mamá grabbed my chin before I had time to rub my eyes. She smoothed my long hair out of my face and gazed at me.

“You are Cecelia Rios,” she said, with a fervor I could feel through her thumbs on my cheeks. “You will be clean and safe, and no one will ever take you away. You will burn as bright as any descendant of the Sun god, and no curse will change that.”

I stared at her. For a moment, I was seven years old again, watching her broken expression. But there was a new and darker depth to the cracks in Mamá’s strength this time. Cracks that spelled out my big sister’s name.

I nodded, trying not to cry.

“Bien.” She dropped her hands and scooped up her bag from the counter. She passed by Dominga del Sol without looking at her. But Dominga del Sol didn’t seem surprised.

It was like Mamá didn’t want to acknowledge her. Like she was afraid that doing so would be admitting that my abuela had faith in the curanderas and their old magic, and that somewhere, deep down, she did too. But with the way the townspeople felt about curanderas—and me—it made a lot of sense. Even if it was pretty rude.

“I have to get to the fields now, mija,” she said. “Dry yourself in the daylight, where the Sun god can claim you. But don’t let anyone see you when you leave here!”

She shut the door behind her and disappeared into the gray of coming dawn. I stood there, dripping like a wet rat. I didn’t have time to dry out in the sun. Every moment I wasn’t looking for Juana was another moment our familia was broken.

Silent tears ran down my face and mingled with the basil. My chest shuddered, and I rubbed the limpia out of my weeping eyes. Turning from the door, I found Dominga del Sol waiting with an open towel.

She smiled over the brightly colored cloth. “It is okay to cry, Cece Rios.” She wrapped it around me and rubbed my shoulders down. I looked up into her small black eyes, at the thick wrinkles framing her large smile. The jade beads in her hair rattled as she drew a second, smaller towel over my hair and squeezed the water out. “Familia is one of the worthiest things to mourn over. Your abuela was like a sister to me, you know. I wept for weeks after she died.”

The sun’s first rays broke through the nearest stained glass window. It touched the crown of Dominga del Sol’s salt-and-pepper hair. “Your abuela always felt different, too. She loved the stories her familia left behind, about curanderas and their ancient powers.”

“Mamá doesn’t like to talk about the curanderas,” I said. “Or about Abuela, either.”

Her smile softened into something sadder. “A criatura killed your abuela,” she said. “The Criatura of the Scorpion, who came to take revenge against your tía, Catrina,

the bruja. Your mamá probably doesn’t like to remember it.”

My mind flashed back to the red leather journal. “Did you know my tía too?”

“Yes. She used to like to come to the sanctuary, to light candles to the Sun god.” Her smile fell, just a little. “You have her eyes, you know. But I don’t think you have her heart. If I were to make a guess, I’d say you have the heart of Etapalli, your abuela.”

She said that like it wasn’t a bad thing. Fragile hope filled my chest.

“Dominga del Sol,” I said. “Can I tell you something?”

“Of course.”

“Do you promise not to tell anyone? Not even my mamá or papá?”

Her face grew more serious. “What is it, mija?”

My heart beat faster. “I want to get my sister back. I—I’m going to get my sister back. I don’t know how. But I’m going to find a way.”

She stared at me for a long moment, and my guts churned. I wondered if she’d ever smile at me again after I said something so ridiculous. I was the weakest person in the village. How could I get my sister, the brightest soul in Tierra del Sol, back?

But to my surprise, she just smiled again. “Do you know what a limpia is for, Cecelia Rios?”

It felt like a trick question, but her eyes held no guile. “For cleansing,” I said. “Mamá says it’s supposed to help fight the power of the water curse Tzitzimitl put on me, to make sure my soul’s fire isn’t put out.”

She folded the towel she’d used to dry me. “A water curse. That’s an interesting choice of words.” Her smile widened. “You see, a limpia is old magic left over from the curanderas, made of herbs, a chant, sunlight, and clean water. With those ingredients combined, curanderas asked the four gods to purify their souls in preparation for a great quest or battle.” She placed the towel down on the nearest counter. “That means you are ready now, Cece, to take on whatever challenge is set before you.”

I stared up at her, soaking in her words like they, too, were a limpia.

She patted my cheek. “If there is anyone in Tierra del Sol who can do this impossible thing, it is you.”

6

The Path of Brujas

All the way home, I did my best to hold on to the warmth Dominga del Sol had given me. I could do this. There had to be a way for me to get Juana back.

When I arrived, I went up to my room first thing to grab something warm. I tugged on my old woolen serape cloak (it was a bit too small, but I loved its blue and green stripes), determined to set off for the library, the Sun Sanctuary again, or anywhere that might have the answers I needed. Just when I was about to head back downstairs, I noticed Tía Catrina’s red leather diary.

I stared at it hesitantly. When someone in your familia became a bruja, you were supposed to burn all their old belongings and bury them in the desert cerros, to plead for forgiveness. Mother Desert hated brujas, Mamá said, because they enslaved her children, the criaturas.

Legend said the world had been peaceful before brujas came into the world. Coyote created animal criaturas—humanlike beings with strange-colored eyes and the ability to shape-shift into the animals they resembled—shortly after the Sun god made us. And for a while, criaturas and humans shared the desert peacefully.

But one day, an early group of humans stole a few animal criaturas’ souls and enslaved them. These were the first brujas.

At first, this story confused me. Mamá had always counseled Juana and me to take a criatura’s soul if we ever faced one, so we could command them to leave us. But the great difference between this action and a bruja’s, Mamá emphasized, was that you always had to return the criatura soul to the desert after you were safe. If you didn’t, and kept it instead, you would bring down Mother Desert’s wrath.

It was after some of the first humans became brujas that dark criaturas appeared. They were monstrous and more powerful than their counterparts, and they came from the desert to take revenge on all humans because of the brujas’ greed. We’d been enemies ever since.

And that’s why we hated brujas, too. If brujas had left well enough alone, criaturas might not have become our enemies at all.

But I couldn’t resist checking inside the journal—just out of curiosity. It fell open to a random page near the middle.

I hear them whispering all the time now, she’d written.

Everything around me has a voice. Axochitl—oh, that was my mamá—says that I’m messing with old magic I don’t understand. But I’ve tried to ignore them, and the voices don’t stop. The stones in the cerros speak of days long since past. Animals warn me danger is near. The plants whisper of weather to come.

Axochitl doesn’t understand. She’s afraid to. She ignores my voices, and she ignores the way Papá hurts Mamá, and she ignores how Mamá’s mind is going because of it. She wants me to ignore it all too.

The desert’s voices are not so passive. If something hurts them, they fight back. If a coyote stalks a rabbit, the rabbit runs. It doesn’t lie down and accept being eaten. I don’t want to either.

I say this all of course because Carlos asked Papá for my hand in marriage today. Papá doesn’t care that I’ve refused. The wedding is set for after the criatura months are over. But he will find I am no rabbit—I will fight back. I don’t care what it takes anymore.

My fingers trembled as I turned a bunch of pages, landing near the end of the book.

Papá will burn this journal if he finds it. He refuses to understand how my becoming an official bruja tonight is better than the life he wants for me. He would never listen if I tried to tell him about my criatura. My criatura is good. He values me. He protects me with the power I give him, and it is right that he does because I am powerful, and I will never let anyone take that power from me again.

I’ve made him so strong that we’ve won all three rounds of the Bruja Fights. No one has been able to stand against us. And once we win in the finals tonight, even the rulers of Devil’s Alley will see and respect me.

Soon, I will enter Devil’s Alley—and there, I will be a queen.

It ended there. That was the last entry.

I set the book down. Chills ran from the roots of my damp hair to my newly dried toes. The house felt extra quiet as realization hit me.

If all she said was true, my tía, a human being, went to Devil’s Alley.

I snatched the book up again and flipped back through it, suddenly hungry for everything she’d written down. How hadn’t I thought of it before? In school, they’d taught us how to spot brujas who’d lived in Devil’s Alley by their glowing eyes or fangs, but each bruja or brujo was originally human. That meant if I became an official bruja by winning the Bruja Fights, I wouldn’t even have to sneak into Devil’s Alley. I’d be welcomed in. Where Juana was waiting.

This is what I had to do. It was the perfect plan.

Okay, maybe “perfect” was the wrong word. Everyone in town already hated me, and things would be a thousand times worse if they discovered that I was trying to become a bruja.

The first light of the sun slanted in through the window. I lifted my head from Tía Catrina’s journal. The light settled on the concrete sill, where a large red silk rose rested. Juana had made it yesterday while I’d prepared the one she’d worn.

“It’s for when you’re older,” she’d said, when I’d looked confused. “I’ll wear yours this year during the Amenazante dance. And when you dance, you’ll wear mine.”

My throat nearly closed up as I took in Juana’s last gift. My fingers clutched Tía Catrina’s journal. Yeah, this wasn’t a perfect plan. It wasn’t even a good plan.

But if this was the only way I could bring Juana home, then it was worth it.

A few hours later, I plodded through the Ruins outside of the town proper, winding closer and closer to the first stop on my mission.

My knees shook a little with each step. If the graffiti and strange signs painted on the abandoned adobe houses around me were any indication, I was definitely getti

ng closer. I checked Tía Catrina’s journal one last time to see if I was on the right path.

The woman called Grimmer Mother nurtures all apprentice brujas on their path to becoming true brujas. She told me I must meet her in Envidia to become powerful. She said I must meet her there, and then she could teach me how to be a bruja. I hope she’s telling the truth.

Next to the writing was a small, scribbled map. I’d been following it out of town for the last thirty minutes, keeping an eye out for the signs depicted in the journal. Envidia was supposed to be out here somewhere, to the west of town. Partly broken adobe and abandoned ranchos dotted the surrounding landscape. It was hard to believe Tierra del Sol had once been as large as this, before the dark criatura attacks had reduced our numbers.

The illustration led me to the farthest section of ruins from town. I stopped as I spotted an outcropping of nine decrepit buildings, all clustered together strangely, unlike the other houses around them.

The two houses facing me were set so the space between them created an archway. Black charcoal markings had been scraped across their faces, warning people away from the makeshift entrance. A purple papel banner waved over the narrow street, the paper decorated with symbols I didn’t recognize and didn’t really want to. Beyond it lay a narrow path, but shadows hid whatever waited there.

I exhaled nervously and glanced at the warnings on the wall. “I’m going to get myself killed.”

I tried not to think as I forced my feet to move forward. The air seemed to grow colder as I approached the archway. My footsteps reverberated in my ears, or was that just my heartbeat? I swallowed hard as I crossed the entranceway, my hands shaking. The narrow alley closed in on me left and right. The shadows were cold. I was terrified, and it was obvious I didn’t belong here.

But I had to try. If I did this right, I really might be able to get Juana back. Papá would be able to smile again. Mamá would embrace her and me, and she’d be proud of me then.

Or at the very least, she’d have Juana to be proud of again.

I came out the other side of the alley, and just a few steps into the center of Envidia, I realized I was even more out of my depth than I’d thought.

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls