- Home

- Kaela Rivera

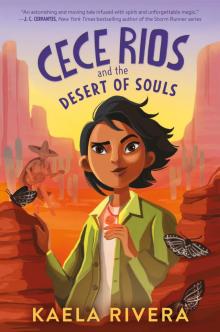

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls Page 5

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls Read online

Page 5

It was pretty obvious by the way the inhabitants looked at me. There weren’t many, only about fifteen brujas and brujos in total. Some sat on the concrete back steps of the old houses while they sharpened their black knives; others leaned against the walls in the shade, stringing together jewelry made of bone. But all of them immediately turned to glare at me as I entered the small space. I froze there, holding my breath. A few looked me up and down. Most of them scowled or smirked. One flipped her knife up and down.

I gripped my elbows, forced myself to move forward, and looked around for Grimmer Mother, the woman Tía Catrina’s journal spoke of.

I didn’t get very far before someone bumped into me.

I stumbled back. Oh no, I’d hit a bruja! Wait, no. Tía Catrina’s journal said only those who’d been accepted into Devil’s Alley and developed fangs and glowing eyes were really called brujas. This girl had to be an apprentice. She whirled around, eyes narrowed to slits. Half of her hair was shaved off, and a bullring piercing hung between her nostrils. She cocked a sharp black eyebrow as she turned to face me, her hand fingering the necklace strap at her throat.

She was only two inches taller than me, but held herself like she was six feet tall. “Do you mind, pollo?” she spat. Literally, I mean. Drops beaded my face.

I tried not to look hurt that she’d just called me a chicken. “Sorry. It was an accident—”

The moment I said “sorry,” her gaze traveled the length of me, taking in my age and lack of a criatura’s soul stone necklace, and met my gaze again with a sharp, predatory smile.

“Oh, you’re an accident all right.” She pressed toward me. I backed away. “What’s a little kid like you doing in the heart of brujería?” She plucked at my serape cloak’s tassels. “Did you get bored? Want to see what a real monster looks like?”

“N-no,” I said. It came out smaller than I wanted, so I swallowed and tried again. “No, I’ve come here to become one.”

She stared. And then laughed. “You’re joking, right? You don’t belong here—”

A hand struck the girl across the face.

My shoulders shot up to my ears as Bruja Bullring stumbled back, holding her cheek. An old woman stood between us now. Her hair was long and black and fell past her waist in a thick, luscious braid. Thin streams of gray ran through it, almost as metallic as her narrowed eyes.

“You fool,” she said to the other girl. “Do you know who this is?”

Oh, my holy sunset. Did this woman recognize me? Bruja Bullring looked somewhere between angry and almost as confused as I was.

The old woman reached for me. I flinched back. Her fingers paused, so the black moths tattooed across her light brown–skinned hands hovered between us. The eyes on their wings moved to watch me. I gasped at the sight.

“You share blood with us,” the woman said. Her mouth curled up on one side, and a thin white fang sliced into view. I bottled up the instinct to scream. Behind her, the girl scampered away. “Don’t you, Cecelia Rios?”

I gripped Tía Catrina’s journal to my chest. I knew who she was—but how did she know me?

“I am Ascalapha Odorata,” she said. Her hand pulled one of mine from the journal and curled around it like a snake constricting. “But you may know me by a different name.”

“Grimmer Mother,” I whispered.

Later in her journal, Tía Catrina wrote about this woman with the tenderness of a student admiring a mentor, and her descriptions made one thing clear—Grimmer Mother was the teacher an apprentice bruja needed if she wanted to win the Bruja Fights and enter Devil’s Alley.

The woman tugged me indoors. Immediately, a plume of charcoal and the smell of burning candles hit my nose. My eyes watered, but I tried to pretend it didn’t bother me. I ended up coughing anyway.

She pushed me down into a cushion on the floor and moved around, shoving blankets, books, and random animal skulls off of the cushion opposite me. Smoke hung in the room like a bad dream.

“You are Catrina’s blood,” she whispered, leaning forward. She took my hands in hers. The moth eyes looked at me again.

Fear traipsed up my back like a cluster of spiders. I shivered. “So, you really are the one who taught Tía Catrina.”

“Yes,” she said, petting my hand. I resisted another shiver. “You have her eyes. And I see,” she tapped the journal, “you have her words too. Now, do you want to travel her path?”

Not even a little bit. But I did want my sister back. So I said, “Yes.”

She didn’t look bothered by how quiet my voice was. “Ay, que bueno!”

She turned away, hunting around the room for something. I let out a shaky sigh. Her grip had been so hot, I could still feel it in my palms.

“You’re cutting it close,” Grimmer Mother said. “The Bruja Fights start in just two days.” She opened a hulking chest and burrowed through it. “You have much to work on. Do you have a criatura yet?”

“Um—no.” I was suddenly very itchy.

She made an annoyed sound. “Just like your tía. A procrastinator.”

Probably shouldn’t bring up the fact that I’d just decided to become a bruja this morning then.

She turned around. Something shone in her moth’s grip. I stiffened as she walked over to me.

“Here,” she said and offered the object. I took it hesitantly. It was a knife, its obsidian blade sharp as winter wind and black as the shadows of a well. “This is the knife I made your aunt use to shave her head. Each apprentice bruja selects a portion of her hair to cut off. It is how you first step into your new life. Your tía cut away the bottom half of her hair.” She eyed me. “Your hair makes your face kind. For you, I suggest removing it all.”

I gawked at her. “All of it?” I’d never cut my hair before, and it was long enough for me to sit on. Papá called it my one great beauty. What would I be without my hair?

“All of it,” she said, with satisfaction this time. “Then you will seem more predator than prey. You can grow it back after you win the Bruja Fights and become a true bruja. Then no one will question you, regardless of your soft eyes.”

But—my ears were going to be so cold. I closed my hands around the knife and tried desperately to keep my expression even. Like I wasn’t dreading the idea.

“You have much gentleness inside you, Cecelia Rios,” she said, and I really wished I knew how she’d found out my name. “You will need more stone inside you to get a criatura’s soul to bow to your control.”

That was going to be a problem since I didn’t have any stone inside me. I almost sighed. No matter where I went, my soul didn’t seem to have what people wanted. Not enough fire for my familia. Not enough stone for brujas. Was water welcome anywhere?

She leaned forward. “Your tía had softness in her as well. But it shriveled quickly once she no longer fed it. You will no doubt be the same.” She smiled, but there was no warmth in it. “Go to the old dried-up silver mine to the south, and travel through what hides beneath. There, you will find the criaturas lurking, and there you will test yourself. Make sure to catch a criatura before Friday night, when the first round of Bruja Fights begins.”

She stood and moved to leave. I jumped up.

“Wait!” I said. “What if I’m not strong enough to control a criatura’s soul once I find one?”

She paused in her doorway, and her mouth split in a grin. “Then the criatura’s teeth will prove you are not worthy to enter Devil’s Alley.” She turned away. “If you survive, return to me. I will teach you how to bend your criatura’s will, body, and soul to your own.”

She left me alone in her house, surrounded by eye-watering smoke. I frowned, stooped, and put out one of her candles. There. Take that, you not-at-all-comforting bruja mother.

“I saw that,” she called.

I hurried to light the candle again.

7

The Makings of a Bruja

A few hours later, secluded in the narrow outhouse behind our home, I dropped Gr

immer Mother’s knife in the steel basin.

My hands shook as I lifted them to my head. The thick strands of heavy hair were gone. My neck was cold and free. I ran both palms over my skull, and a wave of coarse prickles scratched my fingers.

Tears filled my eyes as I looked in the old mirror balanced across the sink.

I pumped my breath in and out. “You’re fine. This is fine.”

I shook my head and swallowed most of the tears down. Even if my head looked like a cactus, this new haircut was exactly what I needed. I looked like I could be a bruja now. That was the first step to actually becoming one.

But a haircut alone wouldn’t make me look like a bruja. I scrambled out of my frilly white dress and serape and tossed them to the side, yanking on my old, roughest, wool shirt instead. Next, I pulled on Papá’s old red buckskin pants. They weren’t exactly flattering, but they were rich in color and attitude, two things I needed. To top it all off, I tugged on Papá’s worn green jacket and played with the holes that riddled its hem. He’d asked Mamá to turn it into cleaning rags last week. Luckily for me, she hadn’t gotten around to it yet. Now I got to enjoy its raw petroleum smell and roomy extra-large size.

The outfit didn’t help me make the same strong impression as the brujas I’d seen in Envidia, but it was close enough.

Except for my face.

I pouted at it in the mirror. I’d always thought my eyes were average, but with no hair to distract from them, they were a large, soft brown, ringed with black eyelashes.

They looked like the eyes of a scared child. Just like Juana had said. Yesterday, she’d teased me about it. Today, she was gone.

I closed my eyes and thought of my hermana. She needed me, so I had to try to look frightening. I pictured her face as El Sombrerón dragged her into the darkness. Listened to her screaming. Calling my name.

I opened my eyes.

With no hair to soften it, my angry face was as welcoming as a skillet. My mouth sharpened into a tough line. My eyes squeezed into menacing, charcoal slashes beneath thick, cutting eyebrows. I’d never seen myself like this.

A knock at the door jarred the expression from my face. “Cece! Is that you in there? I need the bathroom.”

Holy sunset, Mamá was home from the fields. “Just a minute!” I scrambled around, hiding the knife Grimmer Mother gave me in my jacket pocket before sweeping up my cut hair. I gathered the long locks in a thick, massive black ball and hid it in the darkest corner.

“Cece!” Another knock. “I’ve been holding it in for hours!”

I whipped Papá’s jacket off, knife still in the pocket, and shoved it in my small bag. While Mamá continued to knock, I yanked my white dress back on, where it hid the embarrassing buckskins.

“Okay!” I unlocked the door.

She stumbled back as the door swung out. “What were you doing—”

Her mouth fell open. I was about to change the subject when I realized that my hair was shaved off, my dress was rumpled, and all in all I looked like a madwoman.

“Your hair, mija!” she wailed. Her hands leaped to my head, tracing the prickles. “Your beauty! My daughter is a cactus!”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It was just so heavy, and hot, and—”

“Moon above!” she swore in exasperation. “What is happening inside that empty head of yours? Why your hair?”

My mind raced in panic. “I—I didn’t want El Sombrerón to take me too.”

There was a beat of silence, and Mamá’s face softened. “Oh, mija . . .” She stroked my cheek and pressed her lips together. “Pepita, I see. But you have to remember that brujas sometimes shave their heads. The police may get suspicious if they see you like this.” She shook her head. “Everyone already worries about you. And now you do this? So soon after—” Her mouth opened, but she couldn’t say her name. “After—”

“Juana,” I said.

Tears filled Mamá’s eyes until they almost overflowed. Her chin dimpled. I stared. She had never cried during the criatura months. It invited weakness, she always said. And weakness invited death.

Slowly, she shook her head until the tears receded. She pointed back at the house. “Get inside now. You’re grounded. No dinner tonight.”

I straightened up. I’d been looking forward to having her atole—a hot, creamy drink thickened with cornmeal and flavored with sugar and cinnamon. It was warm and comforting, two things I could do with before going criatura hunting.

“But Mamá—” I started.

“You have to think about the consequences of your actions, mija,” she said. “Even if you’re afraid of El Sombrerón, you must think about the message you are sending others. Now is the time for strength.” Her eyes moistened again. “Go to your room.”

I stared at her a moment longer, my mouth hanging open. But I bowed my head and, quietly, stepped outside with my bag, knife, and jacket in tow. Mamá entered the outhouse and closed the door behind her. I trudged across our small backyard and up the steps back inside.

I lifted my head. Wait a second—this was perfect! I grinned and hurried up the ladder to my room. I needed to sneak out to go criatura hunting anyway. This way, Mamá wouldn’t question why I was holed up in my room when I usually preferred to stay by the fireplace in the evenings.

The moment I closed the loft hatch behind me, I pulled off my dress again and put on Papá’s jacket. Next, I opened my small bag and filled it with everything I thought I’d need to catch a criatura—matches, a torch I’d made with old rags and some rancid cooking oil, the knife Grimmer Mother had given me, and Tía Catrina’s journal. Finally ready, I headed to the window.

I waited there for a while, listening for sounds of Mamá returning from the outhouse. A telltale slam of the backdoor and then clanking from the kitchen below told me it was time to escape.

The loft wasn’t far from the ground, but it would still make for a hard fall if I jumped. The house’s exterior wall was nothing but flat adobe. The nearest spot to get my footing was the first-floor kitchen window, where the oven’s smoke pipe trailed out. I might be able to step onto it if I dangled off my sill, but Mamá would see me.

I scowled and scanned the scruffy ground beneath me. There was nothing but tufts of dry grass to cushion my fall. I sighed and leaned back against the wall. There was no easy way out.

A frown deepened between my eyebrows. What, had I thought getting my sister back was going to be easy?

I took a sharp breath and turned to face outside again.

My bag hung heavy on my back. I closed my eyes, gripping the outer edge of the window, and sucked shaking breaths in through my nose. I could do this. For Juana.

I launched myself out of the room, even as my heart twisted up into my mouth.

I hit the ground the way a bird first takes flight—quickly, unexpectedly, and with a scrambling, raw instinct that makes up for lack of experience. I rolled, legs tucked in, and finally hit the fence. I sat up, hand pressed against the unstable wooden posts. For a moment, I could only stare at the window I’d just leaped out of.

Had I really just done that?

My legs shook, but I crouched and ventured ahead anyway. I followed the wall of my house until I came beneath the kitchen window, where I paused, listening. The smell of cinnamon and the sound of a spoon’s steady stirring made it clear Mamá was preparing the atole. My stomach cramped a bit. I crept a little farther before breaking into an all-out run.

My bag thumped against my back as I raced down the street. I still had no idea what catching a criatura entailed, but for the first time in my life, I hoped Mamá was wrong about me—and that Dominga del Sol was right.

It took about half an hour for me to reach the south side of town. I ducked under signs and the old, tattered rope warning that I was about to enter the Ruins and exit the town proper.

Tía Catrina had drawn several maps in her journal. The one that I was following right now led to the old silver mine, where she’d apparently found her criatura

.

I kept myself on track, heading toward where x marked the spot. I knew I was nearing the mine when I passed Criatura’s Well. It was a crooked stack of stones surrounded with signs warning people not to drink from its poisoned water. Stories said a criatura had fallen in it before I was born, and the townspeople had boarded it up to keep it from escaping. Some even said the criatura’s cries could still be heard all the way in the town proper in winter, when the world was quiet.

But I noticed that the boards were broken now. And the exposed hole, decorated with clawmarks in the surrounding stone, was deafeningly silent. I shuddered a little before moving into the mine’s treacherous landscape.

Craggy rock surrounded me, seeming to fill the area, and tunnels punctured horizontally through the ground on each step down. The nearest tunnel opened up on my right, set into the top layer of the mine. The opening was intimidating, dark—exactly the kind of place criaturas might hide. As I ventured toward it, I tugged the stinky torch I’d prepared out of my bag. After a couple of nervous strikes of a match, I got the torch to catch fire.

I stopped in front of the opening, and red light bloomed into the stone tunnel. My heart pounded. Above me and the mine, the sun lowered on the horizon, like a tired man returning home. If I wasn’t careful, I wouldn’t be so lucky.

I entered the tunnel. The ground sloped downward almost immediately. My feet grew heavier with every step I took deeper into the earth, and after about ten minutes of trekking into the darkness, I heard scuffling and hissing sounds. I held my breath. Criaturas.

I pulled the torch as close as I could without burning myself and took Grimmer Mother’s knife out of my bag. I held it out with my free hand, the way I would to cut onions with Mamá.

I took a trembling breath. “You can do this, Cece.”

The ground finally evened out. It was colder down here than I expected. I gripped my light source as the tunnel walls widened. I came up on a turn and held my breath. The hissing sound came from beyond it.

Something was in here with me. I just had to hope it was a criatura I was capable of capturing.

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls

Cece Rios and the Desert of Souls